By John Fellow, editor of Carl Nielsen Brevudgaven

It is 140 years since the birth of Carl Nielsen, and 74 years since his death. His ascent from a humble background made up of farm labourers and fiddlers on mid-Funen to reach the Parnassus of music as his country's greatest composer is, however, not simply a repeat of the trajectory taken by the artistic phenomenon that was Hans Christian Andersen, 60 years his senior and also from Funen.

One thing we can probably all agree about is that, if we step away from the general amnesia that characterises our present day, the world into which we were born bears little resemblance to that in which, in adulthood and middle-age, we have come to live and work. This was something that Carl Nielsen and his contemporaries could say with particularly good reason. Being among the first to experience modernity, they may have been more conscious of its effects. It is characteristic of Carl Nielsen that, as an older man, he was able to regard it as an advantage that he had come from such humble circumstances and could even say: 'I do not think that money makes people happy. It is more likely to make them stunted and narrow, and it prevents them from fully developing their abilities.' (Samtid, pp. 383 and 470)

Television, computers and the constant stream of new innovations may have altered our world but hardly as fundamentally as water supplies, electricity, motorcars, airplanes, radio, penicillin, parliamentarianism and so on that in their day changed the world and human opportunities. Although Hans Christian Andersen had already written enthusiastically about technical progress and had also explored the problems in this development and spoken of the threat of 'Mr Massen' , it was in Carl Nielsen's time that the broad mass of ordinary people began to influence this development and to reap some of its rewards – for better or for worse. While Andersen and his talent had risen to prominence in spite of his time, the composer's talents developed in part due to his time – and were in part directed against it.

If all the good and evil are not to be laid definitively beyond the bounds of time and attributed to the Fall and expulsion from Eden, development – and complexity – must be said to have arrived in earnest with Carl Nielsen's generation. If we wish to understand ourselves, we cannot avoid considering our immediate past. And if we wish to put our own time into perspective, a concern for the era in which our great-grandparents and great-great-grandparents lived is not the worst place to start. Even though we express the issues differently and have often forgotten their context, we continue to hammer away at the same problems as they did then.

Despite all the progress, some things inevitably lagged behind. Maybe that is why there has been a particular focus on developments in communications both then and now. Hans Christian Andersen, for example, had an interest in the new railways and the first telegraph cable under the Atlantic. In Carl Nielsen's time, it was the telephone and after that the motorcar that went from strength to strength. Carl Nielsen was quickly on board, so to speak, acquiring a car in 1924 and, the year before his death in 1930, even being involved in a traffic accident in which he was seriously injured after colliding with a tram – also one of the period's new creations. By then, the number of cars on Danish roads had reached 110,000, compared to the three million there are today, and they were beginning to present a problem.

As regards the telephone, we know that Carl Nielsen spoke on the telephone for the first time in 1887. At the time he was standing neither by a landline nor in a telephone box but at a 'call station' in Skive, and he asked an acquaintance in Viborg: 'Can you feel from my breath that I have drunk a glass of cognac?' (EDH, p. 54) When he later got a telephone himself, a private phone, he soon had to get a secret number to maintain the peace and quiet needed for his work, and he repeatedly had to get a new secret number when the secret became known to too many. Moreover, it was not installed by his desk but in the hall; it was, after all, such a source of disruption.

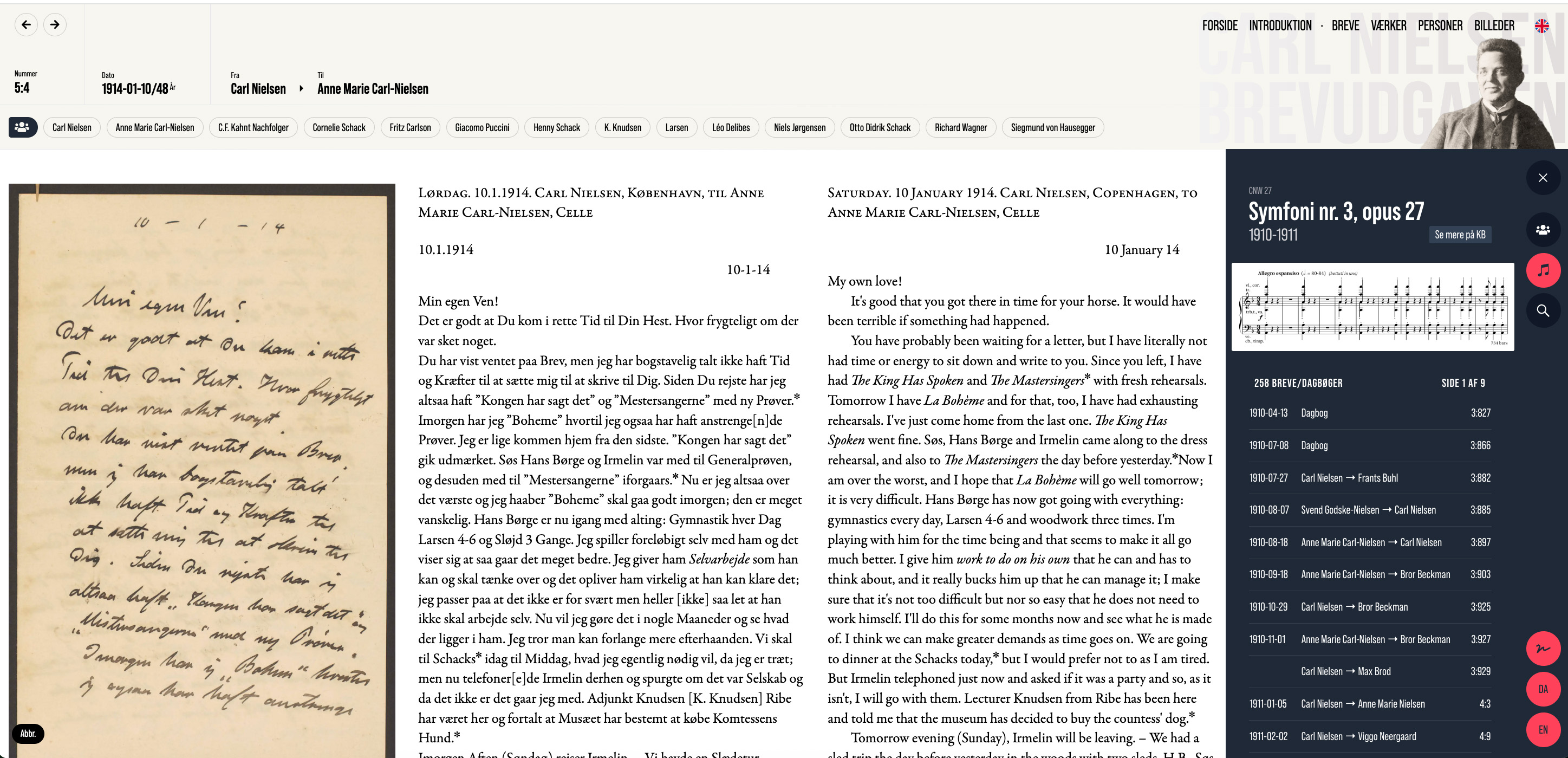

In this first volume of Carl Nielsen's letters, he has not yet got a telephone, but the new form of communication already makes its presence felt in the letters. In a letter from his sister-in-law, an elaborate and expensive telephone conversation from Copenhagen to his wife's childhood home on the Thygesminde farm near Kolding provokes a lively description, which every child born cradling a mobile phone could use to put their understanding and their culture into perspective. [1:675] It is also an old chestnut that the means of communication do not always enhance communication.

For all these new technologies, faced with the sheer quantity of his letters, it is tempting to think that Carl Nielsen communicated with everyone and anyone. He corresponded with people from the social class from which he came and with whom he never lost contact, and people who had scarcely learnt to write wrote to him. As he achieved success as a composer and was appointed to various positions in Danish musical life, he communicated with representatives of pretty much every segment and level of Danish society and with representatives from both Nordic and European musical life, at times in languages in which he was not proficient. What is most important in the present context is that the telephone did not stop him writing letters. There are no signs that the quantity of letters dwindles as the telephone becomes a more everyday feature – rather the contrary.

In other words, Carl Nielsen had other ways of communicating with the world around him than through musical notation. That he was a great composer is common knowledge. However, to explore and acknowledge the full extent and significance of Carl Nielsen the writer and wordsmith is a task reserved for our time. Carl Nielsen's writings comprise more than the little collection of essays Living Music from 1925 and of the memoirs My Childhood from 1927. We have suspected as much over the years from the little collection of letters that appeared in 1954 and from the selection from the diaries and correspondence with his wife published by Torben Schousboe in 1983. The publication of the composer's complete writings and observations in 1999, (The application was signed by Thorvald Aagaard, Emilius Bangert, Jørgen Bentzon, Christian Christiansen, Nancy Dalberg, Svend Godske-Nielsen, Godfred Hartmann, Knud Jeppesen, Ove Jørgensen, Henrik Knudsen, Carl J. Michaelsen, Peder Møller, Thorvald Nielsen, Aage Oxenvad, Adolf Riis-Magnussen, Poul Schierbeck, Rudolph Simonsen), however, made clear the extent of this material and the influence it could have on perceptions of the artist in matters both great and small. This set the scene for a systematic study and a critical edition of the vast mass of correspondence that has been preserved as the last stage in working with source material from the life and work of Denmark's greatest composer.

As parts of his music become increasingly firmly established in Danish cultural life and internationally, as distance grows between us and his time, and as more and more new listeners, musicians, readers, interpreters and researchers encounter him without having the authentic experience of him and of that period that was afforded to those first, now departed, generations, everything about his music and his life and times takes on greater interest and importance – everything that can shed light on and bring us closer to the background, the motivational forces, the circumstances surrounding its creation, whether this be at the private, the personal, the social, the historical or the cultural level. Carl Nielsen is not just one of Denmark's greatest artists; he is one of the few who have touched and been interwoven into its culture so deeply over several generations that Danes cannot fail to be interested in the movements for which he was an influence and a catalyst. Likewise, as a major figure in Europe's cultural life, we owe it both to him and to ourselves to devote our attention to him and his art and to what happened to us and our culture during those years. This attention naturally has to focus around the material that exists, including the large quantity of letters.

The background to this edition of correspondence

A large collection of correspondence like this does not appear out of the blue. It requires the preliminary work to have been done by previous generations. This is what happened in Carl Nielsen's case. In 1935, only a few years after his death and shortly before what would have been his 70th birthday, exactly halfway between the composer's birth and the publication of the first volume of the correspondence, a group of his friends and acquaintances took the initiative to 'honour his character and his art by founding The Carl Nielsen Archive'.

With Carl Nielsen's pupil, the composer Knud Jeppesen, as a central figure, and with advance notice from The Royal Library that they would establish such an archive, approaches were made to those people who had known and been in contact with Carl Nielsen. They were requested, immediately or at a later date, anything they might possess in the form of music manuscripts, letters and the like written in his hand to contribute to, as they put it, 'such a collection as will become a primary source for the study of Carl Nielsen's works and of the story of his life and will create a natural continuation of those collections of written records of prominent composers already in the possession of the Library.' Over subsequent years, new collections of letters from Carl Nielsen have regularly been handed in, not only to the Carl Nielsen Archive but also to several hundred other collections. Of the approximately 3,500 letters written by Carl Nielsen that the collected correspondence has managed to trace, just under 2,000 can be found in The Carl Nielsen Archive.

It is, then, no small number of people who have felt that here there was something worth preserving. The composer's letters were seen as being significant from the very start. Shortly after his death, a few were already published in journals and newspapers and, when the first more substantial biographies appeared at the end of the 1940s, they were based in part on a knowledge of some of the correspondence. This was the case, for example, with the biographies written by Torben Meyer and Frede Schandorf Petersen (Torben Meyer and Frede Schandorf Petersen: Carl Nielsen, Kunstneren og Mennesket, I-II, Copenhagen 1947-48) who were not only able to collaborate with the composer's older daughter, Irmelin Eggert Møller, as a partner, but who found that, for better or for worse, in her capacity as administrator of the family's private archive, she rather adopted the role of project manager (Torben Meyer: Sådan blev biografien "Carl Nielsen, Kunstneren og Mennesket" til, Magazine from The Royal Library, no. 4, March 1998, pp. 27-37). As a close friend of Carl Nielsen over many years, Ludvig Dolleris, who wrote the other major work (Ludvig Dolleris: Carl Nielsen, En Musikografi, Odense 1949), drew to a greater extent upon his own memory and his own sources to a greater extent, not least on his knowledge and understanding of the music.

Nielsen's daughter Irmelin Eggert Møller and the journalist Torben Meyer continued their collaboration, publishing some years later a volume of letters (Carl Nielsens breve, published by Irmelin Eggert Møller and Torben Meyer, Copenhagen 1954). Given the huge mass of material, this was an extremely modest selection, but preparatory work for it extended over several years, and over this period, the two editors worked hard to unearth additional letters from Carl Nielsen's correspondents who were still alive or from their heirs. Some of the newly found letters were passed on to The Carl Nielsen Archive at The Royal Library, while a large number of them were transcribed as extracts and with punctuation and orthography adapted for use in the projected volume of letters, after which the originals were returned to the original owners. The majority of these have since been handed in to public archives. However, despite considerable efforts trying to locate them for the present edition, there is a small proportion that it has not been possible to recover now half a century later. In the case of a few letters, the 1954 edition is thus the only source we have. On the other hand, it must be acknowledged that the preliminary work of these two editors did result in many letters ending up in the archives before it was too late.

The many years that followed saw only a few new and minor publications of source materials and, strangely enough, none that were based on the substantial material that had already been collected in The Carl Nielsen Archive. In 1966, Karl Clausen published Carl Nielsen's correspondence with the Czech writer, Max Brod, (Karl Clausen: Max Brod og Carl Nielsen, Oplevelser og Studier omkring Carl Nielsen, Tønder 1966, pp. 9-36) and in 1980 Niels Martin Jensen published Carl Nielsen's letters to the theatre director Julius Lehmann (Niels Martin Jensen: "Den sindets stridighed –", Breve fra Carl Nielsen til Julius Lehmann, Musik og forskning 6, 1980, pp. 167-185). A more substantial edition of source material came only in 1983 with Torben Schousboe's edition of a selection of Carl Nielsen's diaries and of the correspondence with his wife, the sculptress Anne Marie Carl-Nielsen.

In its way, Schousboe's edition was a decisive breakthrough since it unveiled the violent conflicts that had characterised this marriage of artists over many years. Reading between the lines of brief passages of Meyer and Schandorf's biography and of the daughter Anne Marie Telmányi's memoirs of her childhood home, (Anne Marie Telmányi: Mit barndomshjem. Erindringer om Anne Marie og Carl Nielsen skrevet af deres datter, Copenhagen 1965), it had been possible to sense from some of the ambivalent wording that the marriage was far from idyllic. In Schousboe's selection, however, the marital conflict became the central story and the main theme. This seems paradoxical since the edition had come about as a collaboration with the daughter Irmelin Eggert Møller and based on the family's private archive, which was in her keeping, and it had deliberately aimed to omit anything that was too private.

At the same time, this edition left Carl Nielsen research, which at that time had scarcely got off the ground, in a situation whereby, due to various stipulations, the material presented could neither be assessed or supplemented, while the large quantity of available letters that Torben Schousboe had set aside remained unnoticed and untouched. Michael Fjeldsøe's edition of the correspondence between Ferruccio Busoni and Carl Nielsen was a solitary latecomer on the scene (Michael Fjeldsøe: Ferruccio Busoni og Carl Nielsen – brevveksling gennem tre årtier, Musik og forskning 25, 1999-2000, pp. 18-40).

On the other hand, now that source material was at least extensive enough for interpreters to have something to work with, Schousboe's selection triggered a series of newer biographies, all of which avoided taking on basic studies of source material themselves. The first, largest and most independent, Carl Nielsen, Danskeren ('Carl Nielsen, the Dane'), had even declared its premise that 'after Schousboe's work it is perhaps not so much a matter of uncovering new material as of trying to cast new light on what we already know, biographically and musically.' (Jørgen I. Jensen: Carl Nielsen, Danskeren, Copenhagen 1991, p. 13). One way of realising this programme was to interpret the music in terms of the marital conflict, and at the beginning of the 1990s this view carried such weight that it ended up establishing a norm, though in a less metaphysical manifestation, for the biographies that followed (Steen Christian Steensen: Carl Nielsen, Musik er liv, En biografi om Carl Nielsen, Copenhagen 1999. Karsten Eskildsen: Carl Nielsen – Livet og musikken, Odense 1999).

The story of the couple's marriage even translated into fiction and appeared as a novel (Kirstine Brøndum: Solen mellem tyrens horn, Copenhagen 1996). The first biography in English also appeared as a result of a growing international interest in Carl Nielsen's in music during the last decade of the 20th century (Jack Lawson: Carl Nielsen, London 1997). A large number of errors and misunderstandings were proof that broadening an understanding of his art from a language area as restricted as Danish is especially dependant on the original writings being available, not simply to reflect the views of their time but also as information in a more elementary form.

© Multivers, 2025.

© Multivers, 2025.